Psychologists in New York have had tough working days while assisting folks in surmounting their daily challenges. Here, the emphasis is on “had tough working days.”

The question is, how do they unwind in such a fast-paced city? Culturally, they can showcase all the cuisine New York has to offer, just as one can retreat to Central Park and easily immerse themselves in New York’s ever-growing art scene.

There are many ways to find balance after a hard day’s work. Despite being a highly crowded and busy city, every psychiatrist has their own secret way to calm their minds, away from the clutter.

7 Ways Psychologists In New York Relax After A Long Therapy Session

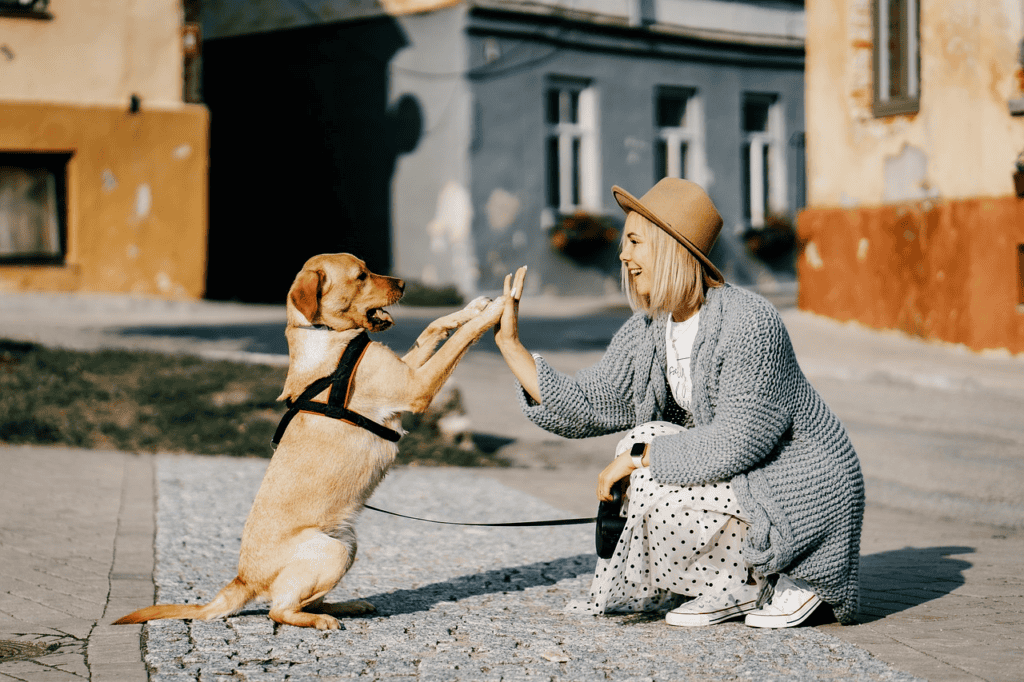

Strolling Through Central Park

Central Park provides great comfort for New York’s psychologists while managing the numerous activities of their day. The constructions of paths, trees, and artificial lakes serve as a perfect combination to calm nerves and restore power.

Occasionally, it might be as simple as going for a stroll, sitting on a park bench to think, or just enjoying the scenery. This is in the case of Central Park, in other parts of the city, the eastern parts to be specific, the park embodies calmness in defeat of the city’s life and its bustle.

Visiting A Local Art Gallery or Museum

Psychological professionals can take operational breaks by simply spending time at an art gallery in New York, and it is indeed a fruitful experience. It helps them redirect their focus to something different and allows them to gather new ideas.

With the Metropolitan Museum of Art and other various smaller galleries in New York, the art world has no bounds. Upon viewing the exhibits, one cannot overlook the colorful paintings and interesting sculptures, which allow an individual to take a cultural detour away from reality.

Practicing Yoga or Meditation

Practicing yoga or meditation helps psychologists in New York to relax after a long work of therapy. For people living in a city whose pulse runs fast, these activities come as a moment of coolness and quietness so as to refresh the brain.

There are many centers in other city sections, so one can always find a place to expand, breathe, and reconnect. This can be a few minutes of stretching and breathing exercises at home or an organized session at a calm studio. There is a tremendous flexibility around yoga and meditation, which makes it simpler to fit them into a busy day.

Enjoying A Quiet Coffee At A Neighborhood Café

According to psychologists in New York, sipping coffee in a quiet café after a long therapy session is a great way to unwind. And who wouldn’t? These corners also have a very quaint combo of hidden gems and small city hustle and bustle.

That warm cup of coffee where city life can leave us momentarily is pure bliss. One can read, write, or just enjoy the quiet; it is a great way to unwind from the everyday chaos and recharge in the middle of expanding civilization.

Attending A Broadway Show or Live Performance

After a long day of conducting therapy sessions, one of the most interesting ways psychologists practice self-care in New York is by going to a live performance or a Broadway show. For them, this form of art allows them to step away from the stresses of life.

The shining lights of Broadway and the different theatres around the city have the potential to enthrall people with great plots, music, and great visuals. Whether it is a high-budget musical or an off-Broadway play, these performances are a great way to rest one’s mind while fueling creativity.

Exploring Wellness Products

A long therapy session could be followed by a session exploring wellness products, which one can say is a hobby for psychologists in New York. This city has a lot to offer through its specialized stores, tea and herbal suppliers, and the internet, which helps people find various products that help them relax.

Some even use natural products like kratom for self-care purposes, along with exploring ideas of how to “order kratom near me in new york”. Interacting with these attention-grabbing products enables the user to have unique experiences and embrace the busy routine with a blend of calm and balance.

Taking A Scenic Ferry Ride or Waterfront Walk

For psychologists in New York, a long therapy session can be followed by a pleasant ferry ride or a waterfront walk, a recreational activity that helps them relax. The city skyline, calm water, and the strong sea breeze can be a good escape from stressful city life.

Moving around on a ferry to the Staten Islands or walking around the Hudson River greenway is physically active and calming, and one gets enough time to relax and enjoy. Such moments spent beside the water can contrast a fast-paced lifestyle and offer a cool perspective to de-stress and rejuvenate.

Why Should Therapists In New York Relax After A Long Therapy Session?

Therapists in New York need to detach from clinical work after long therapy sessions to have a nice equilibrium in their lives. Aiding all these factors in helping them rest and be with their clients is engaging in activities that bring them pure happiness and tranquility.

Given the fast pace of a city like New York, the possibilities to relax abound, whether sitting in a park for a few minutes, going out to appreciate the local arts, or doing a favorite activity. It is quite ideal for therapists to aim for ‘me time’ as it enables a good distinction between work time and personal time, which helps the therapists remain in touch with the outside world and not feel disconnected.

Closing Lines

Psychologists in New York seem to unwind pretty well after their long therapy sessions, given the many options available in the city. Be it a soothing walk in Central Park, a Broadway musical, or a calm coffee at a corner cafe, these little acts of selfcare are very important. One can only appreciate how New York combines calm and chaos to relax after a long, hard day.