Introduction: The Short Answer

You’ve been diagnosed with scoliosis. Now you’re wondering if a chiropractic treatment can actually help.

The answer isn’t as simple as “yes” or “no.”

A chiropractor can help with scoliosis pain and improve spinal function, but the science on reducing the curve itself is mixed. The chiropractic treatment of scoliosis remains controversial in medical circles. Some studies show promise. Others reveal significant limitations.

Here’s what makes this confusing: many chiropractic websites promise dramatic results. But what does the systematic review of actual research say?

This article cuts through the marketing. We’ll examine real studies, not testimonials. You’ll learn what chiropractic treatment can realistically do for your spine. You’ll also discover what it cannot fix.

We analyzed the scientific literature so you don’t have to. The findings might surprise you.

Let’s start with understanding the type of scoliosis you might have. This matters more than you think.

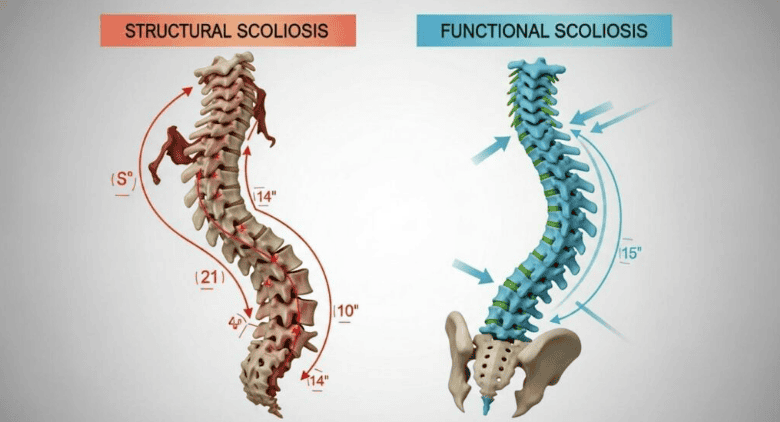

Understanding Scoliotic Curves: Structural Scoliosis vs Functional Scoliosis

Not all scoliotic curves are created equal. The type of scoliosis you have determines what treatment can realistically achieve.

Structural scoliosis involves actual bone deformity in the spine. The vertebrae themselves are wedge-shaped or rotated. This is permanent and cannot be “adjusted away.”

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is the most common type of scoliosis. It develops during growth spurts with no known cause. The curve becomes part of the spine’s structure. Less common types include neuromuscular scoliosis caused by conditions affecting nerves and muscles.

Functional scoliosis is different – it’s caused by muscle imbalances or leg length differences. The spine itself is normal. The scoliosis curve appears because something else pulls it out of alignment. No bone deformity is causing scoliosis in these cases.

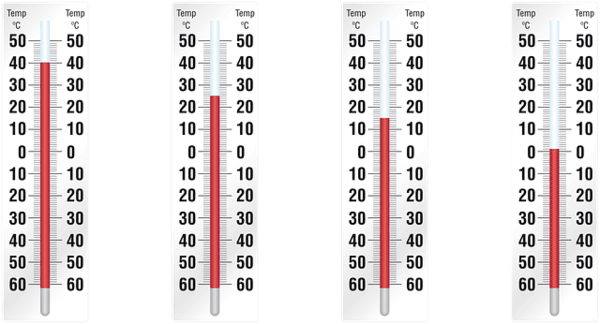

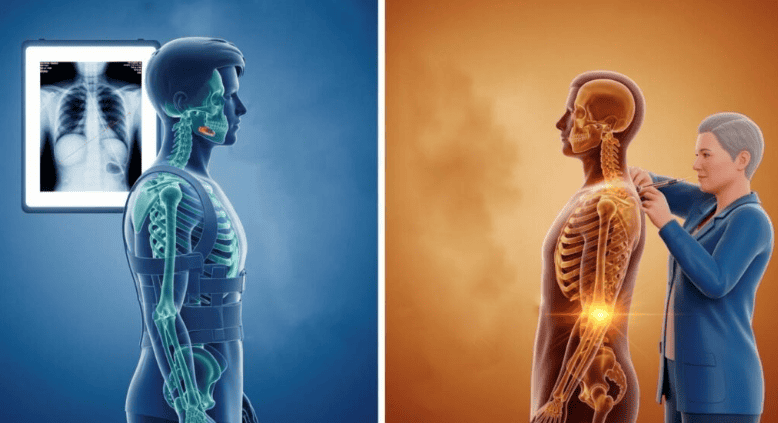

Doctors measure severity using the Cobb angle on an x-ray. They draw lines along the most tilted vertebrae. The angle between these lines shows the degree of curvature.

Chiropractors at Northstar Medical in Downers Grove always recommend taking X-rays for patients with scoliosis, as this is essential for accurate assessment and proper treatment planning.

A curve under 10 degrees isn’t considered scoliosis. Between 10-25 degrees is mild. These mild curves often require monitoring rather than aggressive intervention. The severity of scoliosis determines treatment options. Above 25 degrees requires more aggressive intervention.

Here’s why this matters: functional curves may respond well to chiropractic care. Structural curves? The science tells a more complicated story.

What the Systematic Review Actually Says: Study Design, Cohort Research and Patients Receiving Chiropractic Rehabilitation

Researchers searched databases like Medline to find every study on chiropractic treatment and scoliosis. They also searched CINAHL and PMC for published research. The systematic review of the scientific literature revealed a troubling pattern. The systematic literature showed most studies were low quality.

No randomized controlled trials met the gold standard inclusion criteria. This is the study design that provides the strongest evidence to support treatment claims.

The review of the scientific literature found two types of studies. Some focused on specific treatments of spinal manipulation alone. Others used multimodal approaches combining spinal manipulation and rehabilitation.

The Lantz study used a time-series cohort design published in J Manipulative Physiol Ther. This cohort time-series trial tracked younger patients treated with adjustments over time. Some showed curve reductions. But the cohort was small and lacked long-term follow-up.

For adult scoliosis, one retrospective study examined patients receiving chiropractic rehabilitation for six months. The study design included 28 patients with scoliosis treated with exercises, adjustments, and postural correction.

Results showed improvements in Cobb angle measurements. Pain decreased. Respiratory function improved. But here’s the critical limitation: this was a retrospective case series, not a controlled trial.

The scientific literature shows that many patients treated with chiropractic care report feeling better. Studies published in PMC and BMC Musculoskelet Disord document pain reduction. Pain reduction appears consistent across studies. Organizations like SOSORT (Society on Scoliosis Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation Treatment) emphasize the need for more rigorous research.

But reducing the actual curve? The evidence is mixed at best. Most positive results come from case reports and small cohort studies. These don’t prove causation.

What we need are large randomized controlled trials with proper inclusion criteria. We need two-year follow-ups to see if improvements last. Right now, that research doesn’t exist.

The systematic review concluded that the effectiveness of chiropractic for curve reduction remains unproven. It should not be recommended over treatments that have demonstrated evidence, such as bracing. Not yet, anyway.

How a Chiropractor Help With Scoliosis: Adjustments and Manipulative Therapy

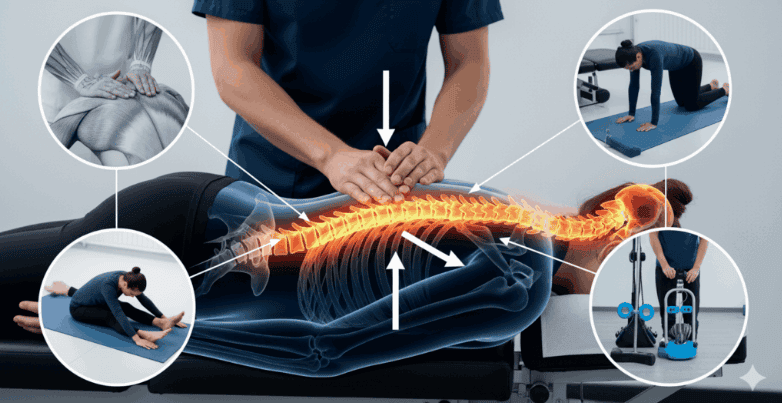

So what exactly does a chiropractor do to treat scoliosis? The approach varies, but certain techniques appear most commonly.

Spinal manipulation is the foundation of chiropractic treatment. Chiropractic manipulation involves the chiropractor applying controlled force to specific vertebrae. The goal of treatment of the spine is to improve alignment and restore mobility.

Chiropractic treatment targets the most rotated vertebrae at the curve’s apex. These manipulative techniques aim to reduce muscle tension around the affected areas. Results from using spinal manipulation vary by individual. Some chiropractors use gentle approaches. Others apply more forceful techniques.

Manual therapy extends beyond simple adjustments. It includes soft tissue work on the muscles supporting the spine. Massage and myofascial release help reduce compensatory tension.

Modern chiropractic management uses a multimodal approach to treat scoliosis effectively. This combines several therapy types rather than relying on manipulation alone.

Rehabilitation treatment strengthens core muscles and improves postural awareness. Patients learn specific stretches targeting their curve pattern. Some programs include breathing exercises to maintain lung capacity.

Additional tools include heel lifts for patients with leg length discrepancies. These heel lifts and postural corrections address biomechanical imbalances. Traction devices may be used to decompress the spine temporarily. Electrical stimulation therapy can reduce muscle spasms. Some treatment programs incorporate lifts and postural and lifestyle modifications for comprehensive care.

The chiropractor typically creates a treatment program lasting several months. Sessions start frequent – often three times weekly. They decrease as progress occurs.

No single therapy produces dramatic results alone. Success requires consistent application of multiple techniques over time.

Chiropractic Management and Treatment for Scoliosis: Adult Scoliosis vs Adolescent Cases (X-Ray Monitoring)

Age dramatically changes how treatment for scoliosis works. Adolescent and adult patients face different challenges and outcomes.

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis occurs during growth spurts, typically between ages 10-15. The curve can progress rapidly as bones develop. This makes early intervention critical. Therapy for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis must account for ongoing skeletal growth in children and adolescents.

For adolescent scoliosis with curves above 25 degrees, a brace remains the standard conservative treatment. The brace prevents progression of spinal curves while bones are still growing. Chiropractic therapy may be added for adolescents with scoliosis but shouldn’t replace bracing.

Curves in the thoracic spine respond differently than thoracolumbar curves. Thoracic curves often progress more aggressively. They may require closer monitoring during adolescent years. Scoliosis can also affect lordosis, the natural inward curves of the spine.

Adult patients face different concerns because their bones have stopped growing. Scoliosis may still progress, but at a much slower rate. Scoliosis progression averages 1-2 degrees per year in adults.

For adults, pain management becomes the primary goal. Conservative treatment focuses on maintaining function and reducing discomfort. A brace rarely helps adults since skeletal maturity has occurred.

Chiropractic therapy for adults emphasizes flexibility and pain relief. The curve itself probably won’t improve significantly. But quality of life often does.

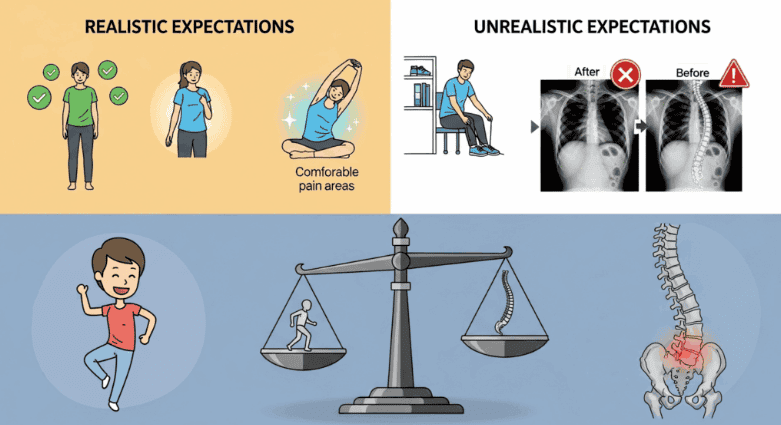

What Chiropractic Care Can Do (and What Scoliosis May Not Respond To)

Let’s be honest about realistic expectations. Understanding what chiropractic care can achieve prevents disappointment and wasted money.

A chiropractor can help with scoliosis pain and improve daily function. Many patients with scoliosis report less discomfort after treatment. The ability to help with pain is well-documented. Muscle tension decreases. Daily function improves.

Chiropractic care often improves postural awareness and balance. Patients learn to move more efficiently despite their curve. This reduces compensatory strain on other body parts.

Flexibility in the spine typically increases with regular therapy. Range of motion improves. Activities that were difficult become easier.

But here’s what chiropractic cannot do: completely straighten a structural curve. Attempts to correct the curve may reduce it slightly in some cases. Expecting your spine to become perfectly straight is unrealistic.

Not every chiropractor has training in spinal deformities. The management of spinal deformities requires specialized knowledge beyond general chiropractic education. General chiropractic differs significantly from scoliosis-specific treatment. A practitioner without specialized knowledge may provide limited results. The chiropractic profession is working to improve standards for scoliosis care.

Some chiropractors claim they can “fix” scoliosis completely. Run from these claims. The science doesn’t support them.

Look for a chiropractor who acknowledges both possibilities and limitations. They should explain how therapy fits into your overall management of scoliosis. They should work alongside your medical team, not against it. A safe and effective approach involves collaboration with other health care practitioners.

The best outcomes combine chiropractic care with other approaches. Exercise, postural training, and sometimes bracing work together. No single treatment cures scoliosis.

Conclusion: The Bottom Line

Can a chiropractor help with scoliosis? Yes, but with important caveats.

Chiropractic treatment can reduce pain and improve daily function. The evidence supports this benefit consistently. If you’re struggling with scoliosis-related discomfort, it’s worth considering.

But don’t expect dramatic curve reduction. The science shows mixed results at best. Proven options like bracing and rehabilitation still lead for adolescent cases.

Choose a chiropractor with specific scoliosis training. Ask about their approach. Request evidence of their results. A good practitioner will be honest about what they can achieve.

Work with your medical team. Chiropractic treatment should complement, not replace, medical monitoring. Regular X-rays track whether your curve progresses.

The bottom line? Chiropractic treatment may help manage symptoms. It’s not a cure. Set realistic expectations and you won’t be disappointed.

.png)